Narramblings #8: Vive la révolution!

Oppression, resistance, and revolution in game stories.

The festive season is upon us. Christmas trees decorated, gifts wrapped, insurance CEOs sho… ah yeah. We’re getting political in this one. Let’s talk about oppression, resistance and revolution in game stories.

I want to focus on two games that have one thing in common — they put the player at the frontlines of rebellion. It’s an inherently political theme, however, blockbuster Detroit: Become Human never managed to craft a compelling political story around it. Where it failed, 1000xResist succeeded despite only having the resources of a small indie studio. How?

First, let’s look at how they paint the political landscape of their stories and then how they treat the player’s agency in it..

Spoilers ahead! For: Detroit: Become Human, 1000xResist

Disclaimer: I’m discussing 1000xResist’s portrayal of oppression and revolution but I’m not knowledgeable enough to get into the specifics of its commentary on the Hong Kong protests. For those interested, I recommend this essay by Kastelpls.

Making the world

Detroit: Become Human is futuristic but it’s a familiar vision of the future, with autonomous cars, electronic newspapers, and whatnot. At the center of the political conflict are androids. When the story begins they’re already a contentious social issue because of skyrocketing unemployment. Things only get more heated from there as the machines start gaining sentience, lashing out against their former masters, and demanding equal rights.

Depicting the androids’ fight for liberation, Quantic Dream again reaches for the familiar, borrowing heavily from the symbolism of oppression of Black people in the US and their struggle against it. Androids can only travel on segregated buses. Their marches and speeches resemble the Civil Rights Movement, with some imagery taken from Black Lives Matter. There is even an equivalent of Underground Railroad smuggling androids out to Canada. Detroit also references the oppression of Jews and the Holocaust.

Those parallels are obvious but never literal, occupying an awkward middle ground. The game doesn’t talk about Black slavery or the Holocaust and never acknowledges those references. Its constant reliance on symbols of oppression is an attempt to make the stakes instantly clear but it’s so hamfisted it becomes unintentionally ironic. A fictional story of liberation told by appropriating real ones.

If you’d like to read a more thorough analysis of cultural appropriation in Detroit, I recommend these essays by Evan Narcisse and Migdalia Melendez.

Detroit tried grounding the player’s understanding of the fiction in its resemblance to reality. This leaves no space for interpretation, because the setting and its political backdrop have been pre-interpreted for us. On the flip side, in 1000xResist making sense of the unfamiliar world is a part of the journey. The story takes place in a post-apocalyptic future, where humanity has been wiped out by aliens known as The Occupants, who brought a deadly pandemic to Earth. The last enclave of humans lives in a submarine city, The Orchard. They’re all clones — Sisters — of Iris, a teenager-turned-goddess known as the Allmother. She was the only person immune to the Occupants and by virtue of that became the saviour. Post-apocalypse and clones aren’t tropes unique to 1000xResist but the whole package is unfamiliar and untethered to anything we know in the real world.

In the first half of 1000xResist we play as Watcher, the Sister whose task it is to study the Allmother’s memories. The game wastes no time letting us know Iris is a false prophet and already in the intro flashes forward to Watcher murdering her. But before we learn how it comes to that, we get to see Iris as an angsty teenage daughter of Asian immigrants who moved to Canada after the 2019 Hong Kong protests. The family memories are the one place where the story shifts from the unfamiliar to literal history. The violence and upheaval Iris’s parents lived through combined with the struggles of immigration were the source of generational trauma she held onto as the Allmother and unleashed on her Sisters. That trauma continues even after she dies. As the Sisters try to contend with the murder of their goddess, they reshape their world and rewrite its mythology only to repeat the cycle of lies and violence. Allmother is replaced by the Provisional Government but instead of dismantling her structures of oppression, they solidify them and create new ones, using propaganda and police. Turns out the weird, imaginary Orchard is shackled by real-world pain.

Unmaking the world

Both games also take the opposite approach to player agency, which is where we really get to dig into their respective views on resistance. Detroit is built on choices. Hundreds of them, big and small, that affect the entire story and dozens of possible endings. Branching isn’t just a narrative system — it is the central mechanic of the entire game. Naturally, this should make for potent political storytelling. Alas.

The game has three protagonists whose stories intertwine, but I’m gonna focus on Markus because his storyline is the political axis of the narrative. You follow Markus’s journey from awakening to leading the movement for android liberation and make plenty of choices that define his relationships and personality. One type of choice, however, carries special meaning. It’s between violent and non-violent approach. During a march, do you want to deliver a message of peace or encourage your fellow androids to fight? When sending a rogue broadcast from a TV station, do you shoot a security guard or spare him? And finally, in the climax, when sentient androids are being killed en masse in death camps, do you demonstrate peacefully or liberate them with force? These choices affect the public opinion of androids and the math is simple: the less violent you are, the more favourable the public, the better the ending.

Detroit gives you a lot of freedom to pick your own path as Markus. At one point you can even choose to take revenge on humans by detonating a nuclear bomb — admittedly bold, especially in a mainstream AAA game. But the story also says loud and clear the only way to freedom is non-violence. Even if you liberate a death camp by force, you get a bad ending. Markus says to other androids: This is not a victory. It’s the beginning of a war. Then we get a cut to the US president announcing her plan to annihilate androids by any means necessary.

The best possible ending — equal rights for androids and peaceful coexistence with humans — happens when you lead a peaceful demonstration at the death camp, which by the way was clearly designed to resemble Nazi camps. You get surrounded by armed cops and they’re about to execute you. If instead of fighting back you sing a song, peace ensues. No, really. The message of non-violence is very consistent and there is something to be said about the sheer technical quality of narrative design on display. To wrangle hundreds of meaningful choices in a way that always forms a coherent narrative with a clear message is impressive. But all this craftsmanship feels wasted on a deeply political story that chooses to be so impotent. The idea that the oppressed can sing nazis into peaceful coexistence is grotesque. Yet again the storytelling in Detroit is an exercise in irony. It promises to give you agency but what agency is this if, when playing as the oppressed, you get punished when you fight back and rewarded when you don’t? A story of revolution washed clean of revolutionary politics.

You’ll see another version of that ending if you don’t have a high enough public opinion. As the song comes to an end, instead of a happily ever after the cops just blast you to pieces in an unintentionally funny moment of vulgar, violent slapstick. It’s a pity the narrative treats this as a bad ending, a failure of the player to score enough points. Executed well this would actually have been a far more powerful message than the ‘good’ ending.

This is way funnier than it has any right to be.

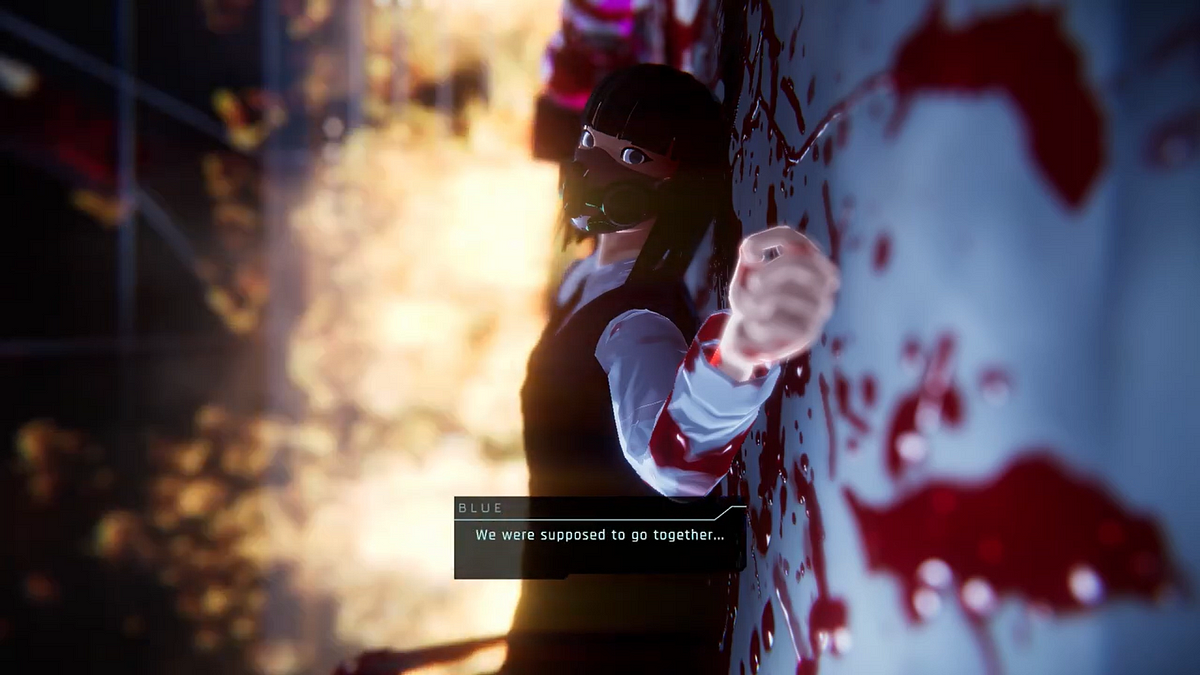

1000x Resist, meanwhile, is a near completely linear story. Dialogue choices are there mostly for the player to learn more about the world or express themselves. After the Allmother’s assassination, you abandon Watcher and continue as Blue, a member of the lowest class of Sisters in the newly established order. When the police murder your friend, it pushes you over the edge and into a conspiracy to take down the Provisional Government. Seeking vengeance, you agree to take part in a bombing. It’s a daring narrative choice. Whereas in Detroit becoming a de facto terrorist is a choice framed unambiguously as wrong, in 1000xResist it’s a part of the plot. And it’s brutal, but not for shock value. The story doesn’t glorify the violence. As you’re trying to escape after conducting the attack, echoes of the Hong Kong protests bleed into the scene. The Orchard, splattered in blood and engulfed in fire, mixes with streets covered in tear gas and crowded with police in riot gear. Fiction meets reality. At no point the violence is a cause for celebration but it is part of a truth that 1000xResist acknowledges and stares at, unflinching. Resistance is violent. Revolution is an ugly, messy, affair and when you take sides, shit and blood will spray on you. You can’t sing nazis into submission.

In the final chapter, you broadcast the Watcher’s and Allmother’s memories in full to all Sisters. The most radical act of revolution is putting the society face to face with its own past and then answering a question about it. What of this past should we take into the future and what to cast away? This is where you finally get to make a choice. The old Sisters, the insurgents, the oppressed, the police, worshippers of the Allmother, even the head of the Provisional Government herself: for each, we get to decide. Do they belong in the future? The game will judge you harshly if you choose to keep the old oppressors or get rid of some of the most oppressed but even knowing that, for each of these choices you need to probe deep inside yourself. Think about forgiveness, retribution, and governance. Ponder how much of the past to allow into the future. Bringing a linear story to conclusion with a big, difficult decision like this is a statement from 1000xResist about revolution and its consequences.

Let’s wrap this up by pulling away from politics because there’s an important lesson here for narrative designers. While branching is powerful as a unique attribute of video game storytelling, it’s not always conducive to giving the story depth and complexity. Compared to Detroit’s vast tree of diverging paths, 1000xResist is almost completely linear. But whereas in Detroit the branching and the multitude of options become the point more so than the story itself, 1000xResist uses the linearity to the story’s advantage. It makes you watch and do horrible things to push you to think about cycles of trauma and violence and how to break them. Someone could argue that 1000xResist was never going to have nearly as much branching as Detroit — not for artistic reasons but simply because Sunset Visitor had a fraction of Quantic Dream’s budget. Alas, I doubt they would have told the story any differently even with plenty more money to spend. Because while 1000xResist is not a big game, it is one of the most intentional pieces of interactive storytelling I have ever seen.